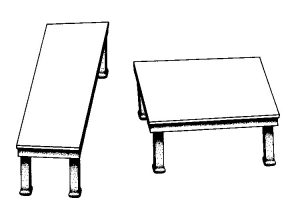

In 1990 in his new book Mind Sights, Stanford professor Roger Shepard first introduced this  image and called it, Turning the Tables. Shepard was fascinated by why humans perceive the same objects differently simply based upon their physical orientation to us. He argued the reason the average human brain thinks they see different sized tables in these images is because as humans we tend to “generalize” our understanding of what’s in front of us from past experiences. It’s the way our evolutionary brains seem to work. And that was our advantage back in the day when we were being chased across the great savannas by large ravenous beasts looking for a meal. But in modern times, the same skill-set can have far less successful ramifications.

image and called it, Turning the Tables. Shepard was fascinated by why humans perceive the same objects differently simply based upon their physical orientation to us. He argued the reason the average human brain thinks they see different sized tables in these images is because as humans we tend to “generalize” our understanding of what’s in front of us from past experiences. It’s the way our evolutionary brains seem to work. And that was our advantage back in the day when we were being chased across the great savannas by large ravenous beasts looking for a meal. But in modern times, the same skill-set can have far less successful ramifications.

A faulty generalization for example is a conclusion based on limited sample size. For example, let’s say you go to Vegas and bet on lucky 7 at the roulette table, they spin and you win $10,000. Chances are good that given that single victory you will immediately generalize that your lucky streak has arrived and bet again. To Shepard over time these innate human behaviors “have become so deeply internalized, implicit, and automatic in their operation as to be largely inaccessible to our conscious awareness.” In other words, humans simply can’t walk away from the table, and as a result over time develop dozens of unhealthy biases to support our knack for creating generalizations.

Decision Biases in Business

In his widely popular 2011 book Thinking, Fast & Slow, author Daniel Kahneman (notable decision theory expert) linked our tendency to generalize with the concept of Heuristics in decision-making. Heuristics are like rules of thumb we humans learn and use over time as short-cuts to making quick decisions and moving on. Learning and teaching these heuristic (rules of thumb) especially from elders and leaders undoubtedly enabled humans to survive and thrive because they helped us identify a safer way to live such as which plants to use as medicine, or when and where to hunt for food, build temporary shelters, and anticipate weather patterns and seasons. But while many Heuristics can prevent calamity others, which accumulate in our psyche over time as these authors suggest, become biases, and it’s these deeply rooted biases that can cause great harm when making key business decisions.

Perhaps the most damaging of all biases is not what you might first think, it’s not race, religion, gender, or social status that tops the deadly list, it’s actually “Overconfidence,” aka executive hubris. And in business and life we see it everywhere because it’s synonymous to being a “risk-taker,” a person who takes a chance that the expected outcome they perceive will occur is greater than any other. But that’s not all. Coupled with that overconfidence bias is “speed.” Speed alone is not a bias, but when combined with overconfidence it’s like mixing drinking and driving making fast decisions particularly damaging or even deadly. And as humans no matter how many thousands of years have passed, we can’t seem to turn it off.

For example, on January 27th 1986, the night before the Space Shuttle Challenger was scheduled to launch from the Kennedy Space Center in Florida, the temperature out at launchpad 39A was unusually cold that morning, below freezing for the first time in a long time. Still, under pressure from NASA to keep the program on schedule the contractor who built the solid rocket boosters, Morton Thiokol, proclaimed their rockets could handle the freeze as senior program managers gave NASA the green light. The hubris had come from the simple idea that no other rocket had failed to launch in the cold weather before. Consequential, neither would this one the executives told NASA. That overconfidence, which killed seven astronauts is “the mother of all biases” according to Max Bazerman & Don Moore authors of Judgement in Managerial Decision Making (2013) and is responsible for much of the world’s worst human-driven preventable disasters whose rival is only that of mother nature herself.

The same can happen in mergers & acquisitions, which are notorious for not working out as intended. And it was hubris and overconfidence that were center stage when in January 2000 CEOs Gerry Levin of Time Warner and Steve Case of then giant online access provider AOL decided to merge. AOL actually acquired TW using its overvalued stock at the time. The deal was estimated at $165 billion, still among the largest ever. But only a few short months later as the dot-com boom collapsed, so did the hubris and confidence at which time AOL was forced to write-off $99 billion of the deal value the following year which in turn helped to collapse AOL’s market valuation from $225 Billion to $20 billion, essentially laying off hundreds of workers and wiping out 90% of the company’s market value. It remains among the leading M&A disaster case studies of all time.

I use these two extreme examples to showcase that there is no size limit to how deadly the impact that overconfidence can have. Small companies are equally at risk as large ones whose CEOs jump to conclusions heuristically believing their own personal insights and successful tract records will never lead them astray on their road to Vegas. And they may be right most of the time, but when they are wrong, the fallout can put everything on the line. So how do we attack this problem?

How to Overcome your Biases

According to Kahneman, the best way to avoid making a bad decision that might be driven by one or more of your personal biases as a leader is to block your biases at the outset. The way to do that is to “recognize the signs that you are in a cognitive minefield, slow down, and ask for reinforcement,” which simply means to step back and give your biases a chance to reveal themselves and their prospective positions and impact on your decisions. This is the concept behind Kahneman’s thinking fast vs slow. Thinking fast is how we all got here, but thinking slow is how we make the most of it better, not the other way around.

It is believed by many in retrospect that had history’s most eventful decision-makers understood this deep human flaw and taken measures to step back from their heuristic biases and generalizations beforehand, dozens of history’s most bias-driven damaging decisions could have been avoided. And for most of us having that ability to step back and pre-judge our decisions objectively might help us avoid pulling the trigger at the wrong time, and in turn suffering the consequences we never expected.

Make sense?

Rick

About the author: Rick Andrade is a Food Industry investment banker at Janas Associates in Pasadena, where he helps Food CEOs buy, sell and finance middle market companies. Rick earned his BA and MBA from UCLA along with his Series 7, 63 & 79 FINRA securities licenses. He is also a CA Real Estate Broker, a volunteer SBA/SCORE instructor, and blogs at www.RickAndrade.com on issues important to middle market business owners. He can be reached at RJA@JanasCorp.com. Please note this article is for informational purposes only and should not be considered in any way an offer to buy or sell a security. Securities are offered through JCC Advisors, Member FINRA/SIPC.